Digital Solargraphy

28 Mar 2020If you want to capture your own digital solargraphy images, have a look: Digital Solargraphy

Solargraphies (pinhole images on photograhic paper that capture months of the sun arching across the horizon) were a thing starting sometime in the 200Xs (the first decade of the century(?), whatever…). When this caught on broadly in the early 201Xs it got a lot of people excited for film again. Quite a few people apparently started dropping cans with paper and pinholes in woods and the public urban space and I very much like this idea.

Solargraphy.com (run by Tarja Trygg) is collecting hundreds of wonderful examples.

A few other relevant links:

- Interview with Tarja Trygg: lomography.de

- Interview with Jens Edinger about how to build (and hide) pinhole cans [in german]: lomography.de

- Flickr Solargraphy Group: flickr

- Motorized Solargraphy Analemmas: analemma.pl

- People are even doing timelapses with them: petapixel.com

- one of the very few examples (actually the only one I could find) of digital day-long sun exposures: link

- Some Solargraphies I very much like are from Jip Lambermont: Zonnekijkster

- Most of the analogue landscape/city images of Michael Wesely could be called Solargraphies, too.

While these pinhole cameras built from beer cans and sewer plumbing tubes have a very appealing DIY character, you can even buy them off-the-shelf by now (boo!).

No, I’m kidding. Offering pre-assembled kits makes solargraphies way more accessible and having easy-to-build hardware is certainly something this project lacks.

However, I really like film (or paper in this instance) but I got rid of all my analogue equipment. For a reason: it’s horrible to handle. So, how about doing the same but without film?

Theory

The problem:

It’s easy to create digital long exposures. Reduce the sensors’ exposure to light and let it run for a few seconds. If you want to go longer you will realize that after a few seconds it will get horribly noisy. The next step up in the game is taking many single exposures and averaging them. This way an arbitarily long exposure can be simulated quite well in software. When using a weighted average based on exposure value from the single images, even day long exposures are possible. Nice! Except that won’t work for solargraphy images. While the sun burns into the film and marks it permanently, the extremly bright spot/streak of the sun is averaged away and won’t be visible in the digital ultra long exposure. Darn…

24 hour digital long exposure:

result:

So, how can we solve this problem? While taking single exposures we need to keep track of the spots of the film that would be “burned” or solarized. For every image we take (with the correct exposure) we take another image right away with the least amount of light possible hitting the sensor. We assume that every bit of light that would have hit the sensor in our second, much darker exposure would have been sufficiently bright to permanently mark the film.

Lets take a step back for a moment and talk about EV or Exposure Value. A correctly exposed image done at 1s with f/1.0 and ISO 100 has an EV of 0. Half a second with the same aperture and ISO settings is EV 1, quarter of a second EV 2, … So Wikipedia lists a scene with a cloudy or overcast sky at about EV 13, a cloud-free full sunlight moment at EV 16. A standard (DSLR/mirrorless) camera reaches about 1/4000th of a second exposure time, most lenses f/22 and the lowest ISO setting is either 25, 50 or 100. 1/4000s @ f/22 and ISO 100 is equal to EV 20 to 22. So we can use EV as a way to describe the amount of brightness in a scene (if we would expose it correctly) and – at the same time – as a measure of whats the maximum amount of brightness a camera can handle without overexposing. Basically how many photons are hitting the camera and how many photons can the camera successfully block during exposure. Whats the EV value to (reliably) determine which parts of the film would have been permanently marked? Generally, as a rule of thumb: the clearer the sky, the less clouds, the less haze, the less particles and water droplets in the atmosphere that reflect light, the lower the max EV value of the camera may be. So, can a camera at 1/4000s with aperture 22 and ISO 100 capture so few photons that we can assume that a certain part of the image is extremly bright: sometimes. Every piece of cloud that gets backlit by the sun gets incredibly bright and if the camera is not able to step down/reduce the brightness sufficiently it’s impossible to reliably determine if this spot would have been bright enough to leave a mark (spoiler, it wouldn’t, but it’s impossible then to differentiate between a bright cloud and an unblocked view of the sun.) To step down to EV 20 suffices only for very clear days, if unknown conditions are to be expected (nearly always in europe sadly), then at least 24 is required in my experience.

However, there is an easy way to move the window of min/max possibly capturable EV values by the camera: a neutral-density filter. That reduces the amount of light that hits the sensor considerably, so the camera won’t be able to capture images in the dusk or dawn or the night, but that’s not a problem in our case since these images wouldn’t be relevant for a multi-day long exposure anyway (compared to the bright daytime their impact on the overall image is negligible). When using a ND64 filter (64 or 2 to the power of 6) it takes away about 6 EV (ND filters are never precise) and thus gives us 26 as the max EV value. How does that look?

Correctly exposed image (EV: 11)

Slightly darker (EV: 14)

Close to what most DSLRs achieve out of the box (EV: 19)

Aaaand here we go (EV: 26)

Does that suffice: I would say, yes.

Software

So, how to process this? Take a correctly exposed photo every X seconds and a second photo at EV 26 right away too. From all the first photos the long exposure image is calculated by doing a weighted average based on metadata. We can calculate the EV value from the EXIF data of the image, apply an offset to the value and use 2 to the power of the offsetted EV value as our weight for averaging pixel values.

For the set of second images we can’t do that, we would average out all burned image sections/pixels. There we just overlay every image and keep the brightest pixels of all images.

Afterwards we take the long exposure image and burn all the bright pixels with the data from our sun overlay:

Terrific! But how many images are required and how fast do we need to take them?

Interval duration depends on the focal length (the wider the image, the smaller the sun, the longer the time in between images may last). In my case for a wide angle image (about 24mm) 60s seem to be the minium and 45s would be preferrable. If the interval exceeds 60s the arc of the sun is reduced to overlaying circles and finally just something like a string of pearls. One way to cheat is by applying a bit of gaussian smooting on the sun overlay image to help break up the hard edges and smooth out the sun circles.

90 second interval:

(gaps are caused by a partially clouded sky which blocked the sun)

(gaps are caused by a partially clouded sky which blocked the sun)

The number of images for the long exposure depends on the amount of movement but a number of 60 to 90 images works well even for tiny details.

Hardware

Tada?…

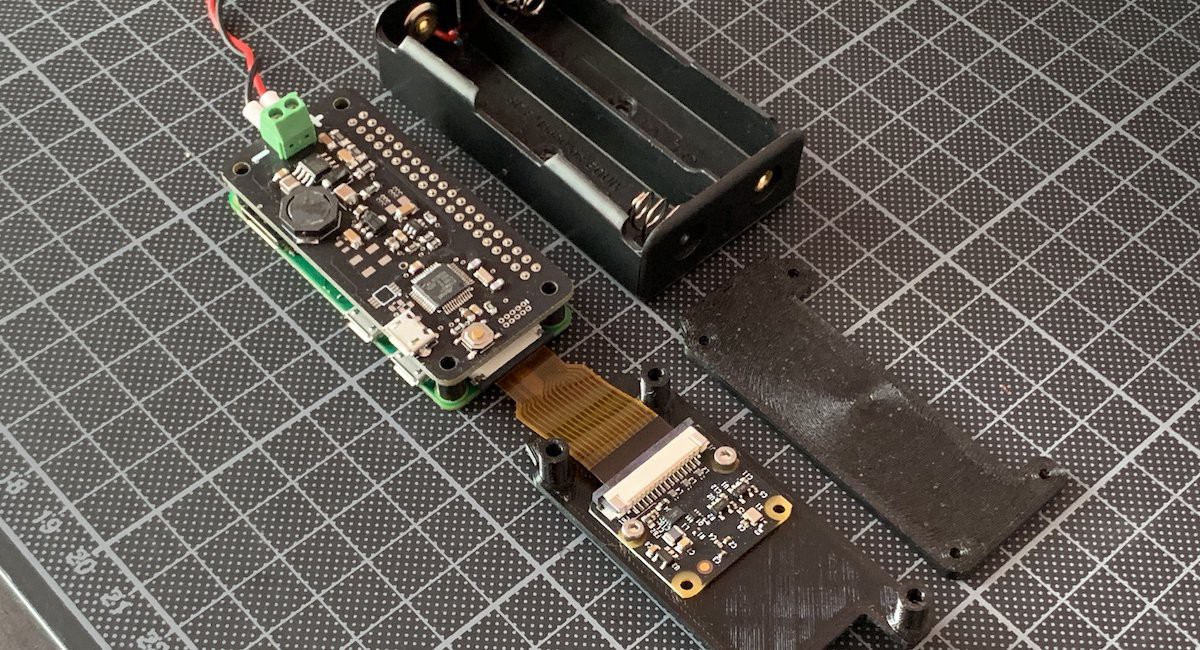

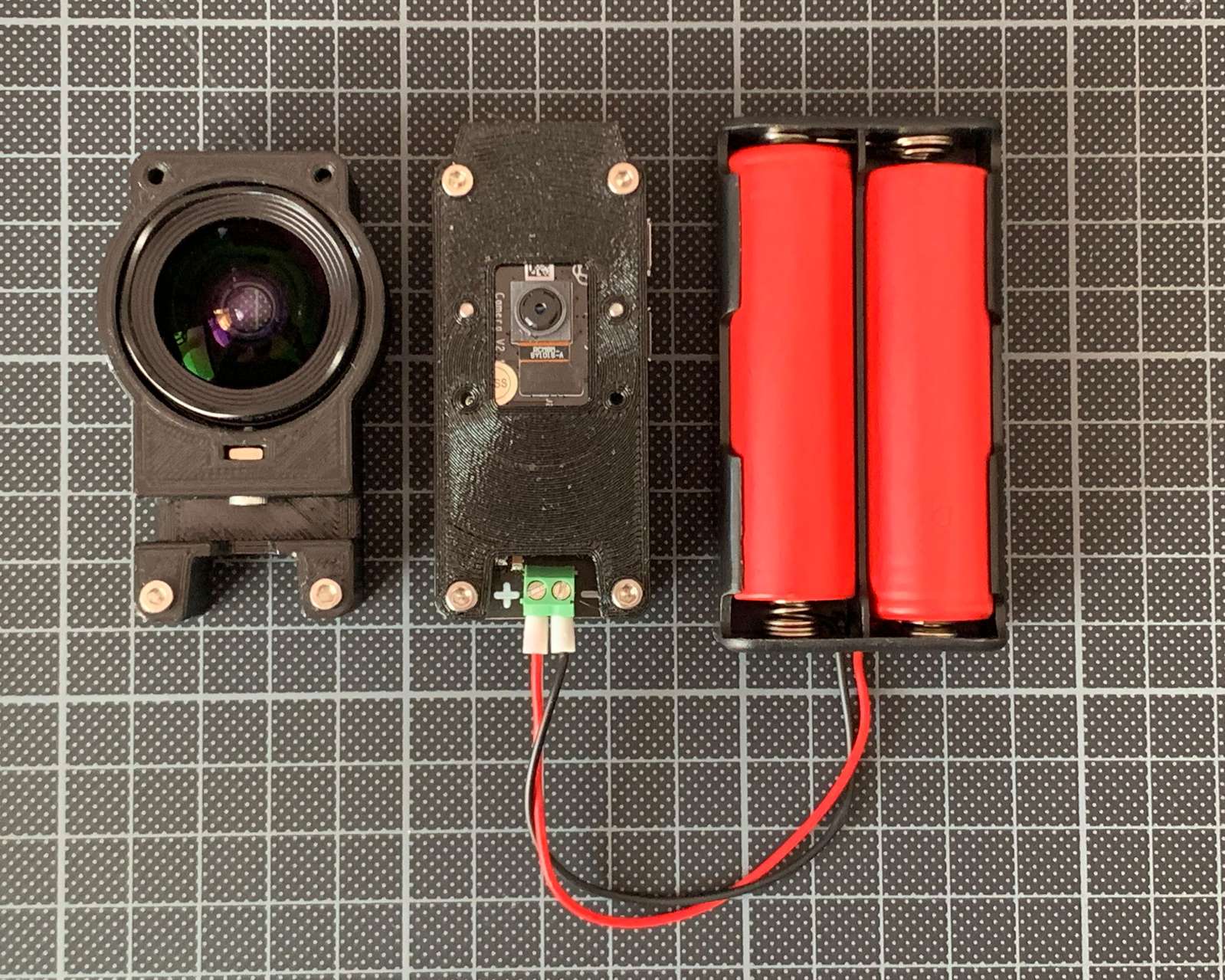

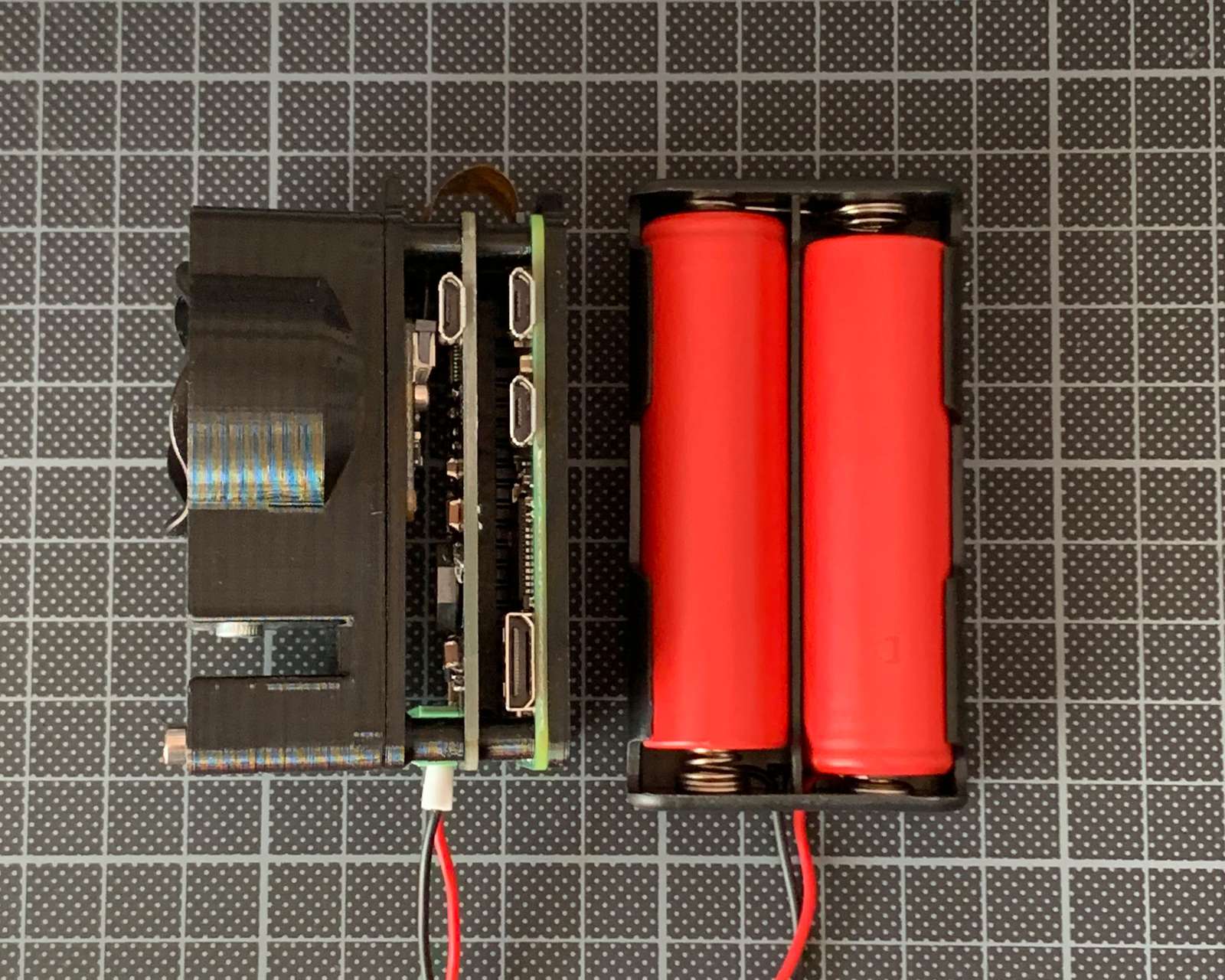

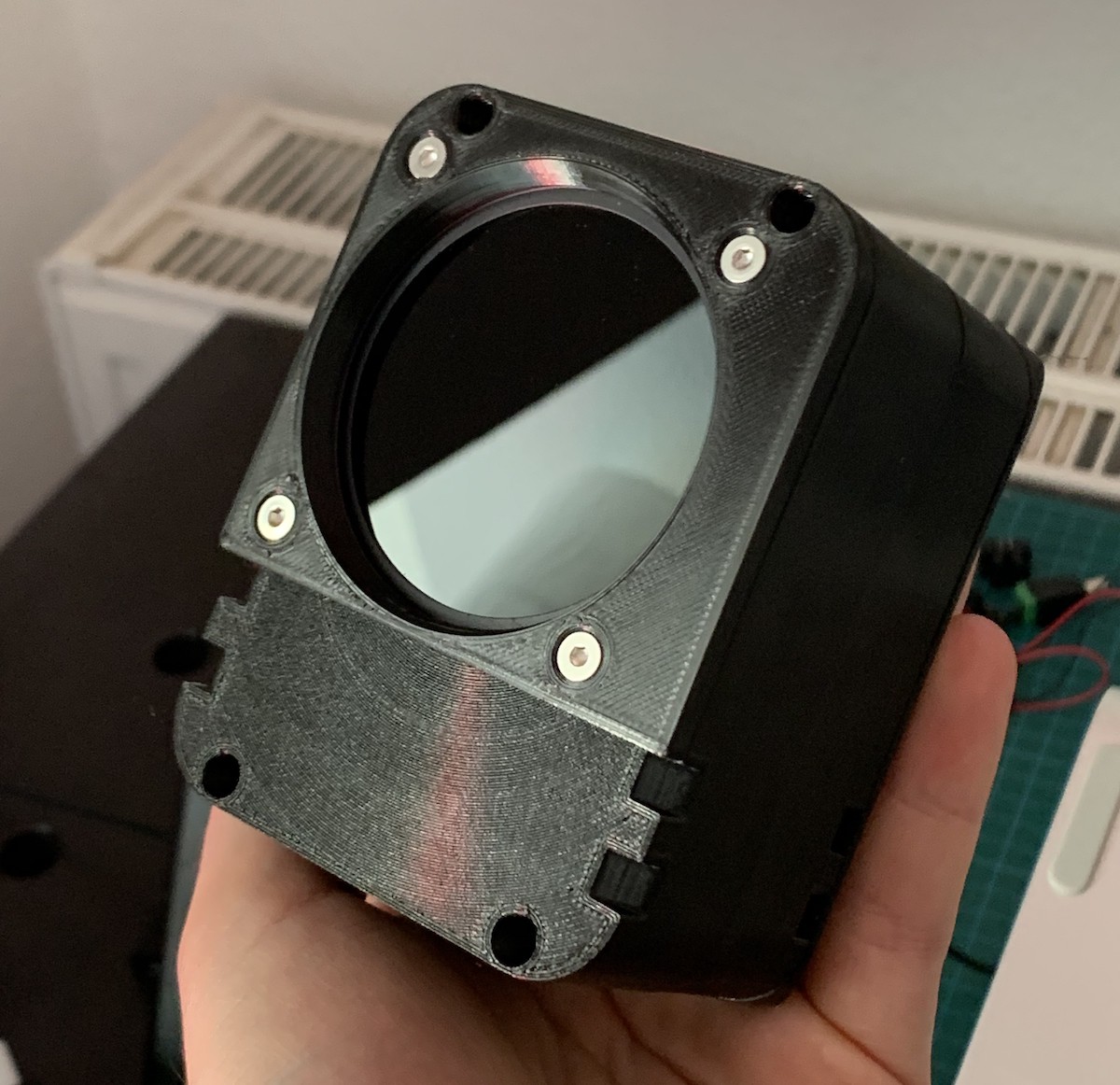

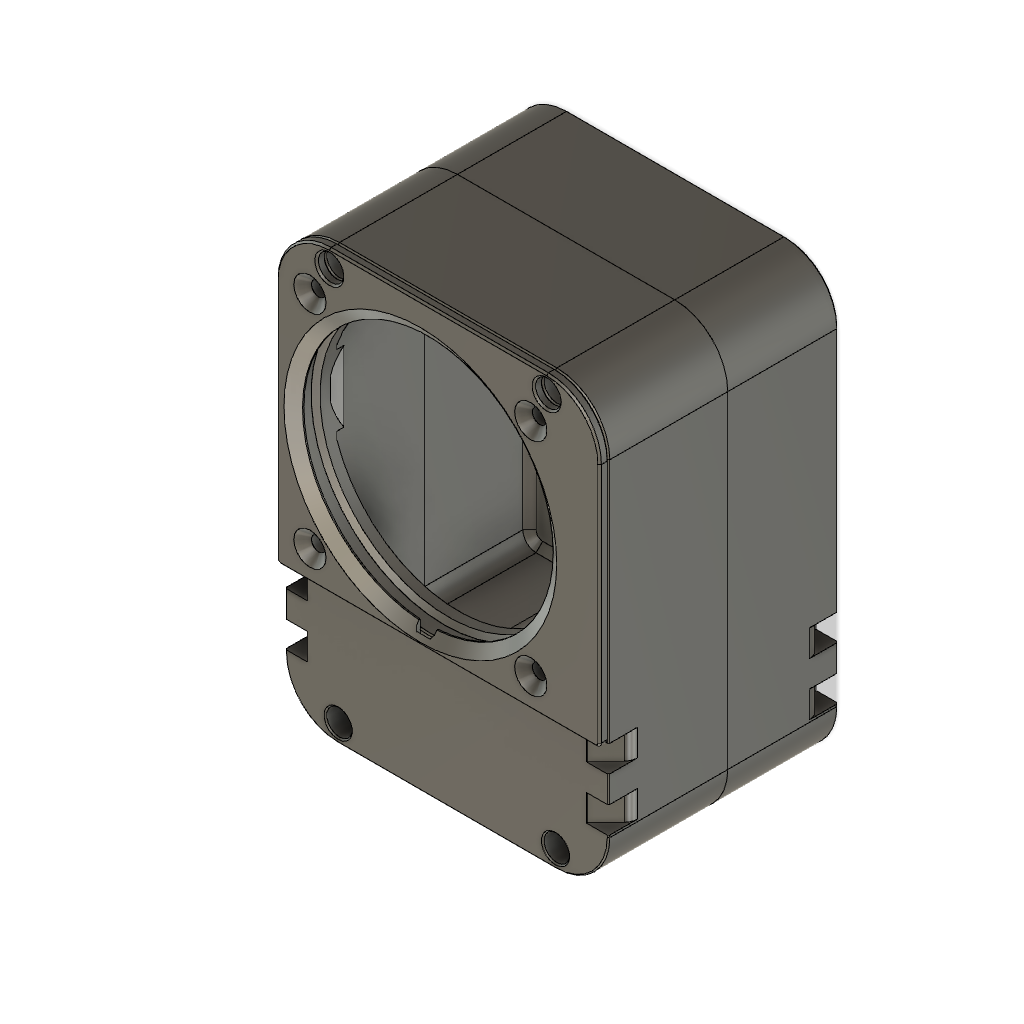

Nice. We got a feasible way of creating a digital solargraphy. Except, we need to actually take/make one. How to get a (relatively) disposable camera out there that may be snatched away by pesky birds or even peskier public servants at any moment? Some solargraphy enthusiasts report 30 to 50 percent loss of cameras when placing them out in the wild for half a year (winter to summer solistice, i.e. highest to lowest point of the sun). I won’t do six months, but being prepared for losing a camera or two might be a good idea. The smallest and least expensive camera I (you?) can build is basically a Raspberry Pi Zero with a Pi Camera Module. That’s featuring a whoppy 8 megapixels but I guess that’s ok, we don’t want this to be ultra-sharp glossy fine-art prints. Combined with some electronics for turning it on and off to take a picture-pair at given intervals, a battery, a smartphone attachment lens and some horribly strong neodym-magnets we wrap this in a 3D-printed enclosure.

A bit of technical details: a Raspberry Pi hat featuring a SAMD21 microcontroller (the Arduino Zero chip) draws power from two 18650 batteries and switches the Pi on every 60s (if it’s bright outside) or at slower intervals if the camera reports less light. The pi boots, takes a few images and powers off again. The system is powered by the batteries for 2.5 days, generating about 10gb of data per day. In order to be fast enough to boot the system, measure the light, take several images, save them and power off in less than 60s the pi runs buildroot, a minimal linux distro instead of the bloated Raspbian.

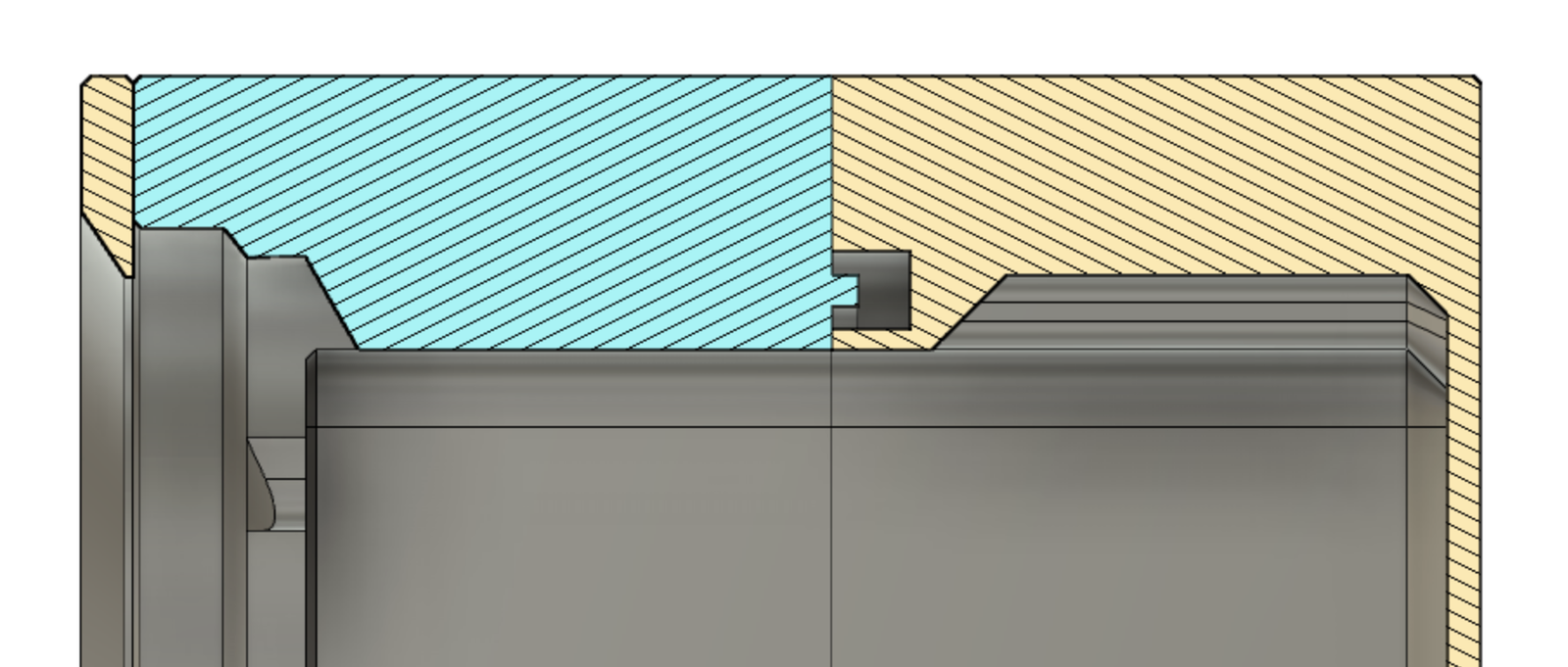

Getting the 3d printed box weatherproof is the hardest challenge when building this. I’ve had good results with a seal of 3mm very soft EPDM rubber string in a 3mm cavity.

Images

Examples from Weimar:

Caveats and flaws:

To determine burned parts/pixels I use a one-shot approach. Either exposure on a single image did suffice to permanently leave a mark or it didn’t. No cumulative measure is used in any way. If there is traffic and cars in the image, this results in a low-fidelity reproduction of the behaviour of film exposures. While reflections by glass and metal of the cars would result in a flurry cloud of tiny specks of burn-ins over a long amount of time on film, the punctual noise of only a few dozen or a hundred digital exposures using the one-shot method is less appealing to the eye. A good example of how this looks on a film image is this image from Michael Wesely. But: that’s something for another day.

“I want to do this too!”

Cool! However: Some assembly required. I may write a post with some more detailed info at some random time in the future. Resources for now:

-

The software I use for stacking, averaging and peaking is on github but please be advised: it is not exactly plug’n’play.

-

Eagle board files and schematics for the 2S Lipo Battery Raspberry Pi Hat can be found here

-

Fusion360 files for the watertight enclosure can be downloaded here

Got questions? Drop me a line.